Are Face Masks Effective? The Evidence.

Updated: October 2021

First published: July 2020

An overview of the current evidence regarding the effectiveness of face masks.

Contents: A) Published studies ⇓ B) Real-world evidence ⇓ C) N95/FFP2 masks ⇓ D) Additional aspects ⇓ E) The aerosol issue ⇓ F) Contrary evidence ⇓ G) Mask-related risks ⇓ H) Conclusion ⇓

A) Studies on the effectiveness of face masks

So far, most studies found little to no evidence for the effectiveness of face masks in the general population, neither as personal protective equipment nor as a source control.

- A May 2020 meta-study on pandemic influenza published by the US CDC found that face masks had no effect, neither as personal protective equipment nor as a source control. (Source)

- A Danish randomized controlled trial with 6000 participants, published in the Annals of Internal Medicine in November 2020, found no statistically significant effect of high-quality medical face masks against SARS-CoV-2 infection in a community setting. (Source)

- A large randomized controlled trial with close to 8000 participants, published in October 2020 in PLOS One, found that face masks “did not seem to be effective against laboratory-confirmed viral respiratory infections nor against clinical respiratory infection.” (Source)

- A February 2021 review by the European CDC found no high-quality evidence in favor of face masks and recommended their use only based on the ‘precautionary principle’. (Source)

- A July 2020 review by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine found that there is no evidence for the effectiveness of face masks against virus infection or transmission. (Source)

- A November 2020 Cochrane review found that face masks did not reduce influenza-like illness (ILI) cases, neither in the general population nor in health care workers. (Source)

- An August 2021 study published in the Int. Research Journal of Public Health found “no association between mask mandates or use and reduced COVID-19 spread in US states.” (Source)

- A July 2021 experimental study published by the American Institute of Physics found that face masks reduced indoor aerosols by at most 12%, not enough to prevent infections. (Source)

- An April 2020 review by two US professors in respiratory and infectious disease from the University of Illinois concluded that face masks have no effect in everyday life, neither as self-protection nor to protect third parties (so-called source control). (Source)

- An article in the New England Journal of Medicine from May 2020 came to the conclusion that face masks offer little to no protection in everyday life. (Source)

- A 2015 study in the British Medical Journal BMJ Open found that cloth masks were penetrated by 97% of particles and may increase infection risk by retaining moisture or repeated use. (Source)

- An August 2020 review by a German professor in virology, epidemiology and hygiene found that there is no evidence for the effectiveness of face masks and that the improper daily use of masks by the public may in fact lead to an increase in infections. (Source)

For a review of studies claiming face masks are effective, see section F) below.

B) Development of cases after mask mandates

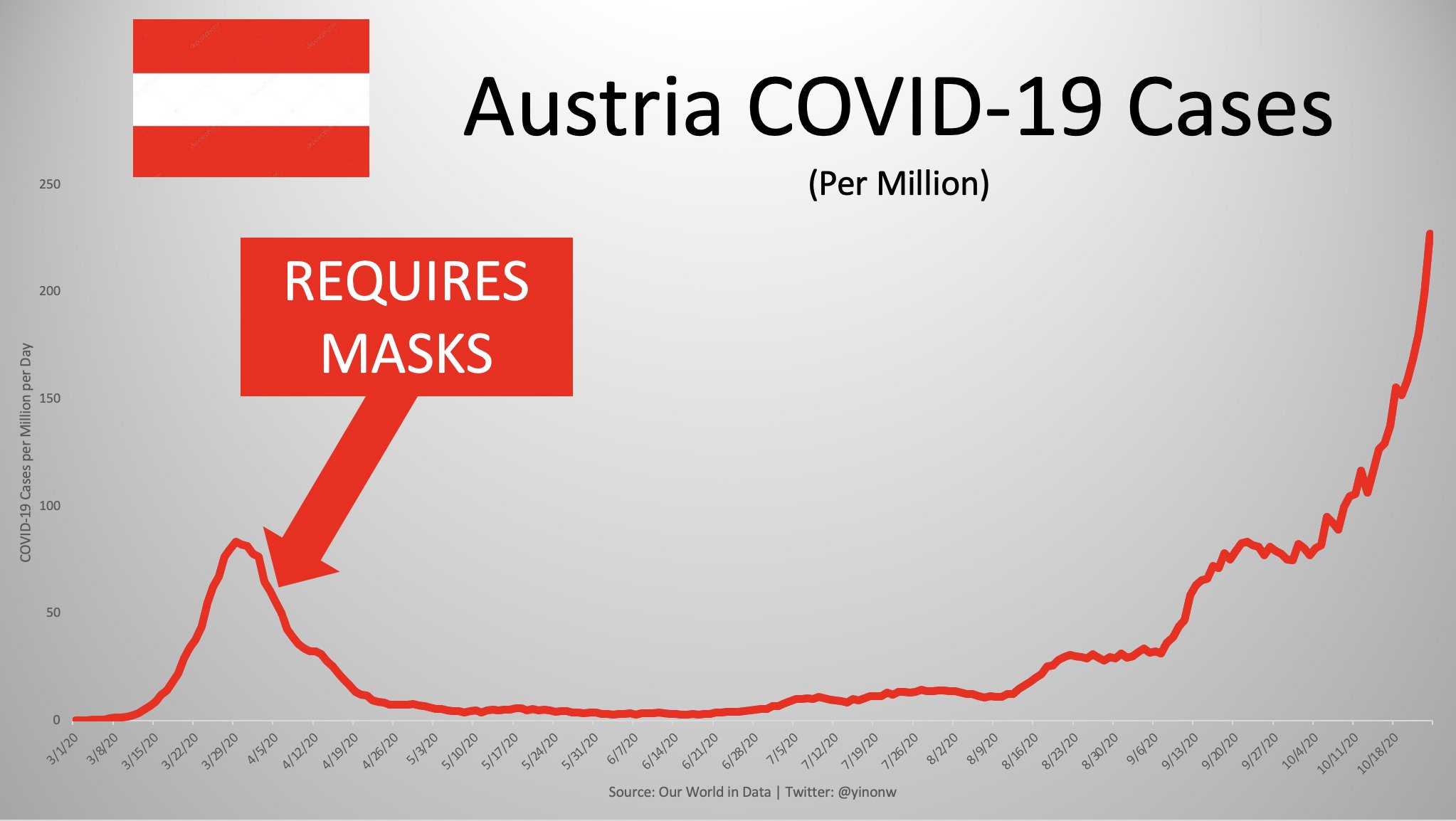

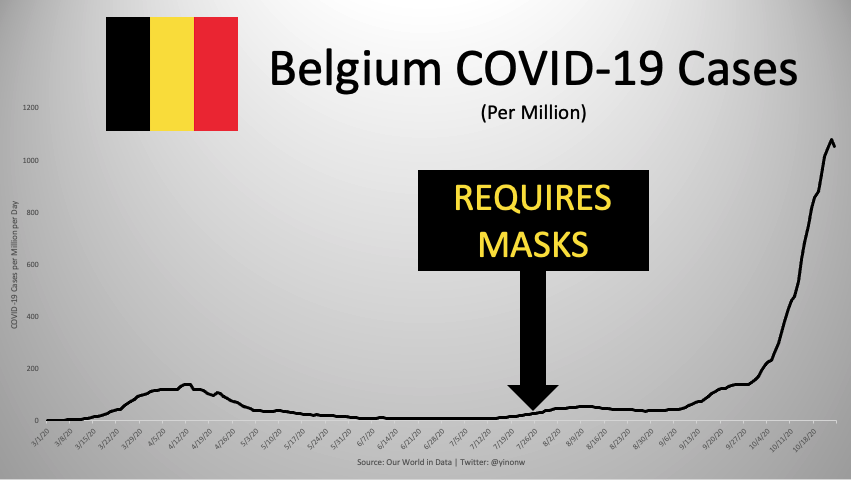

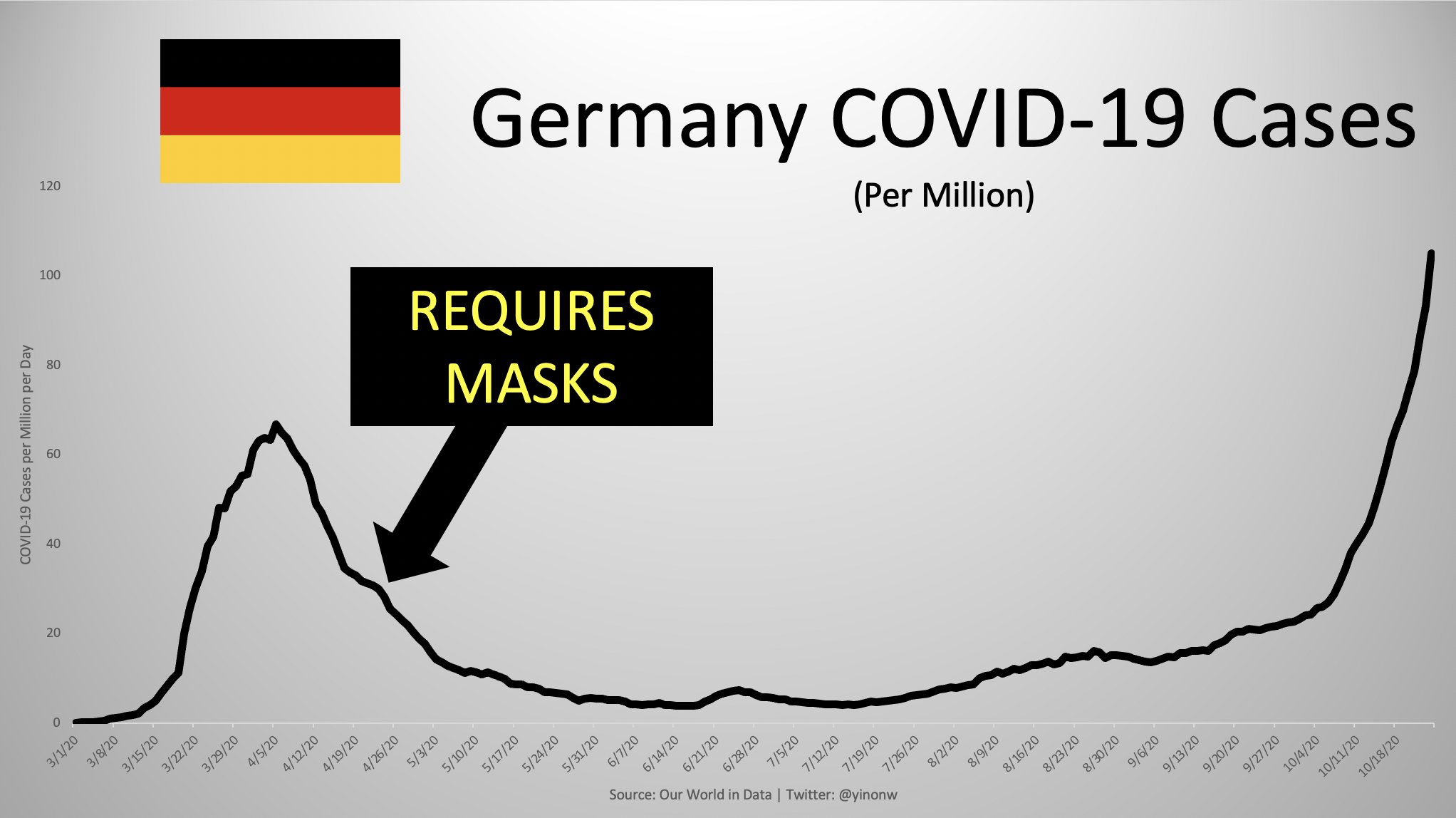

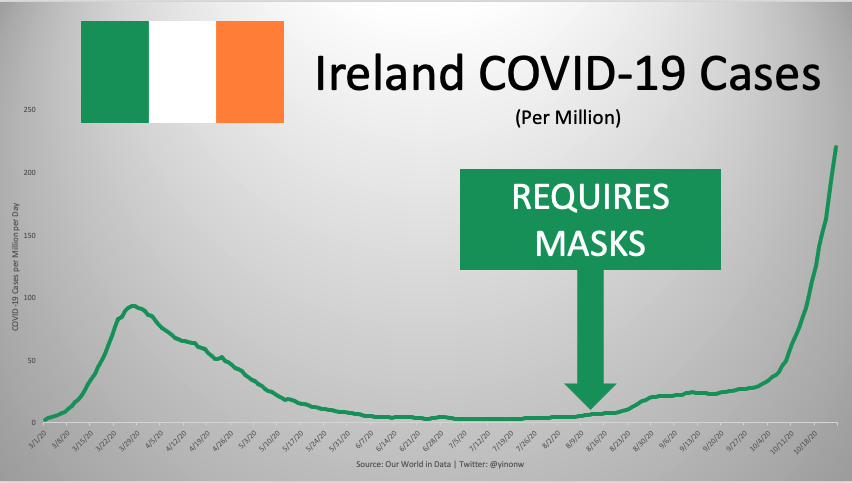

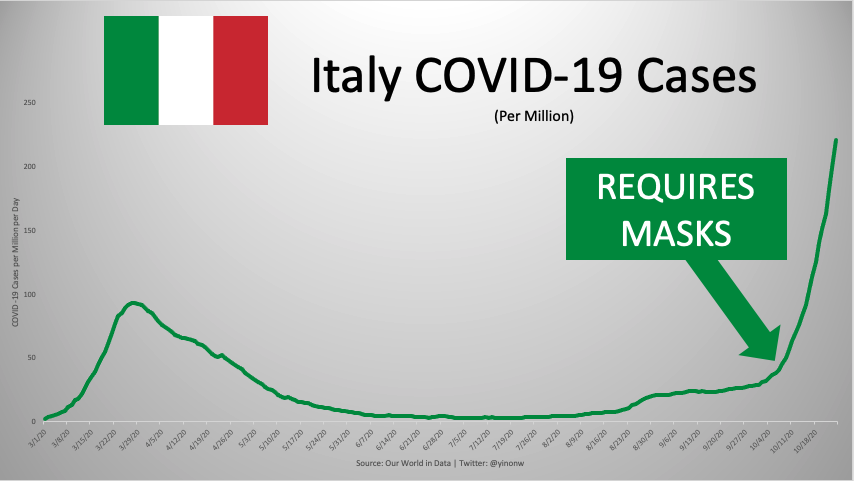

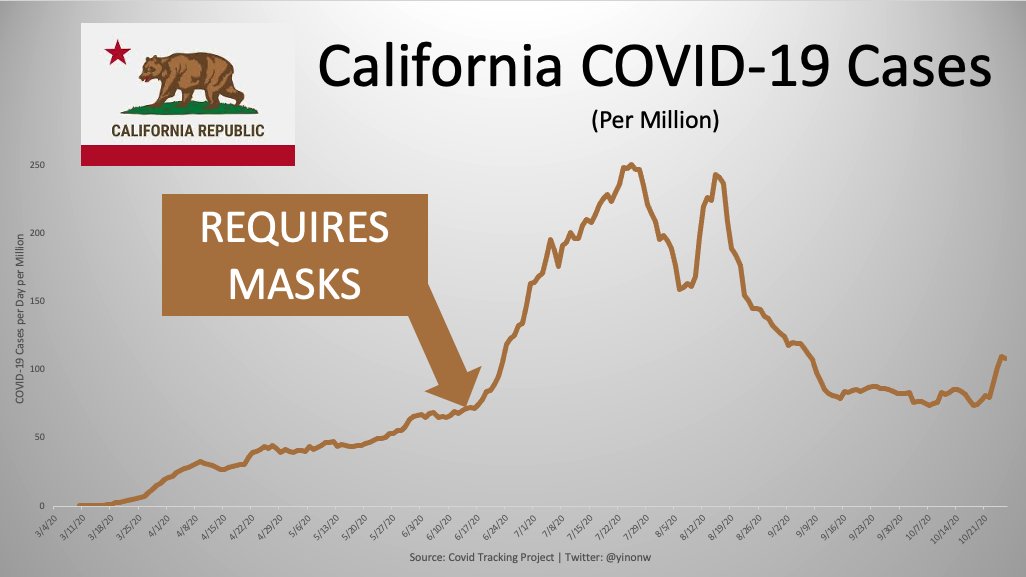

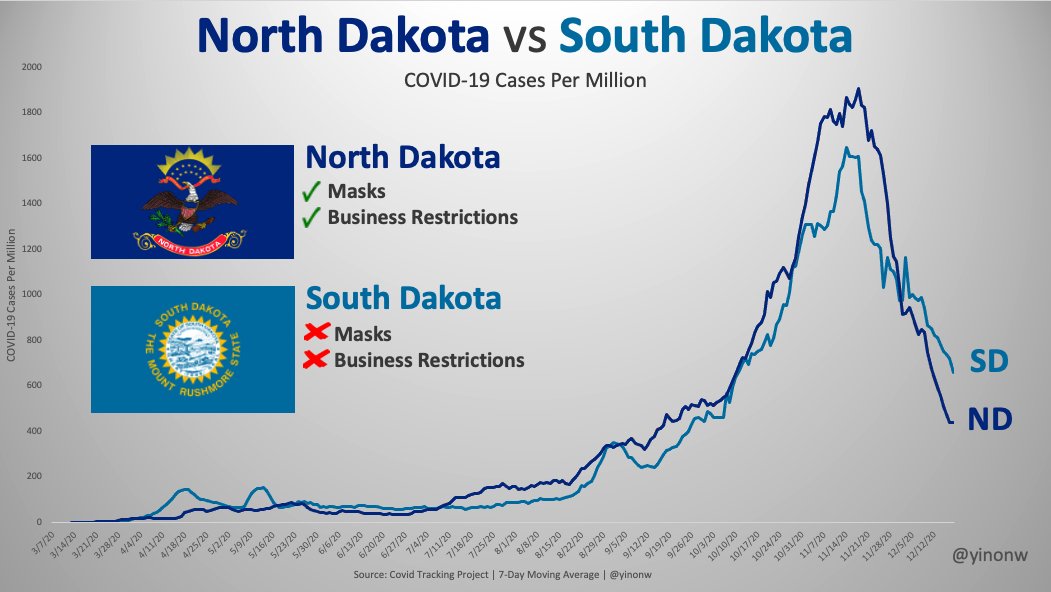

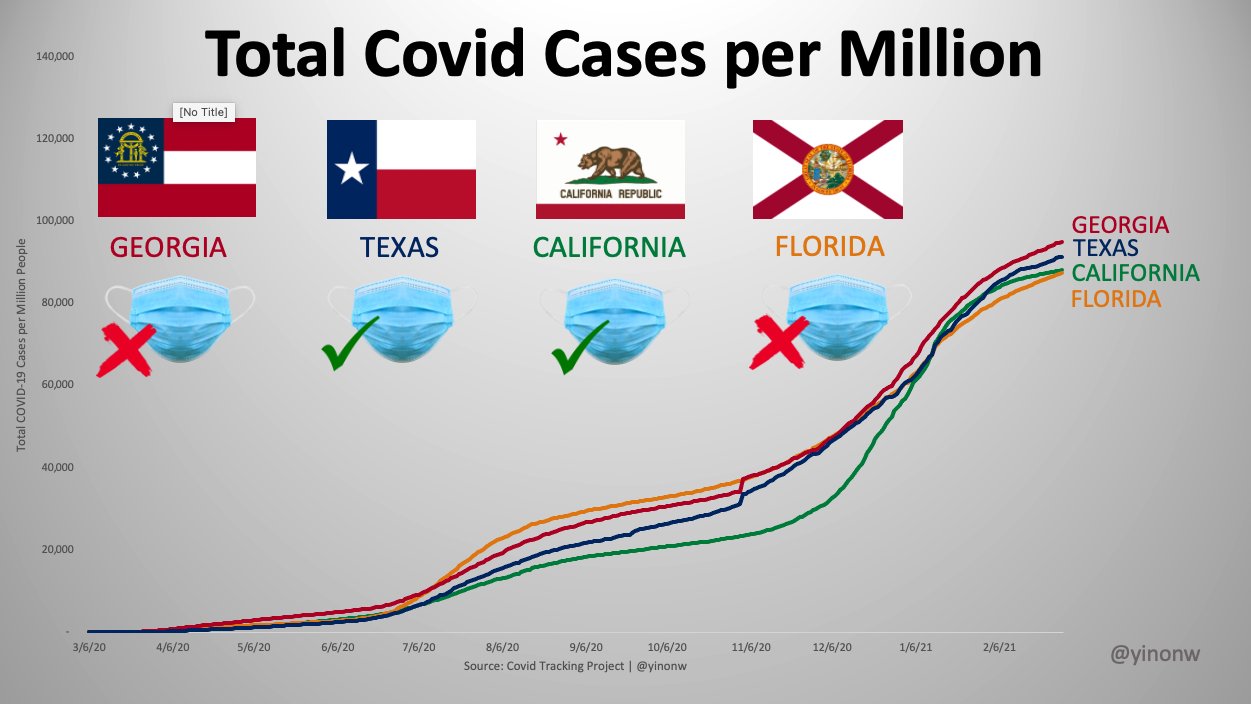

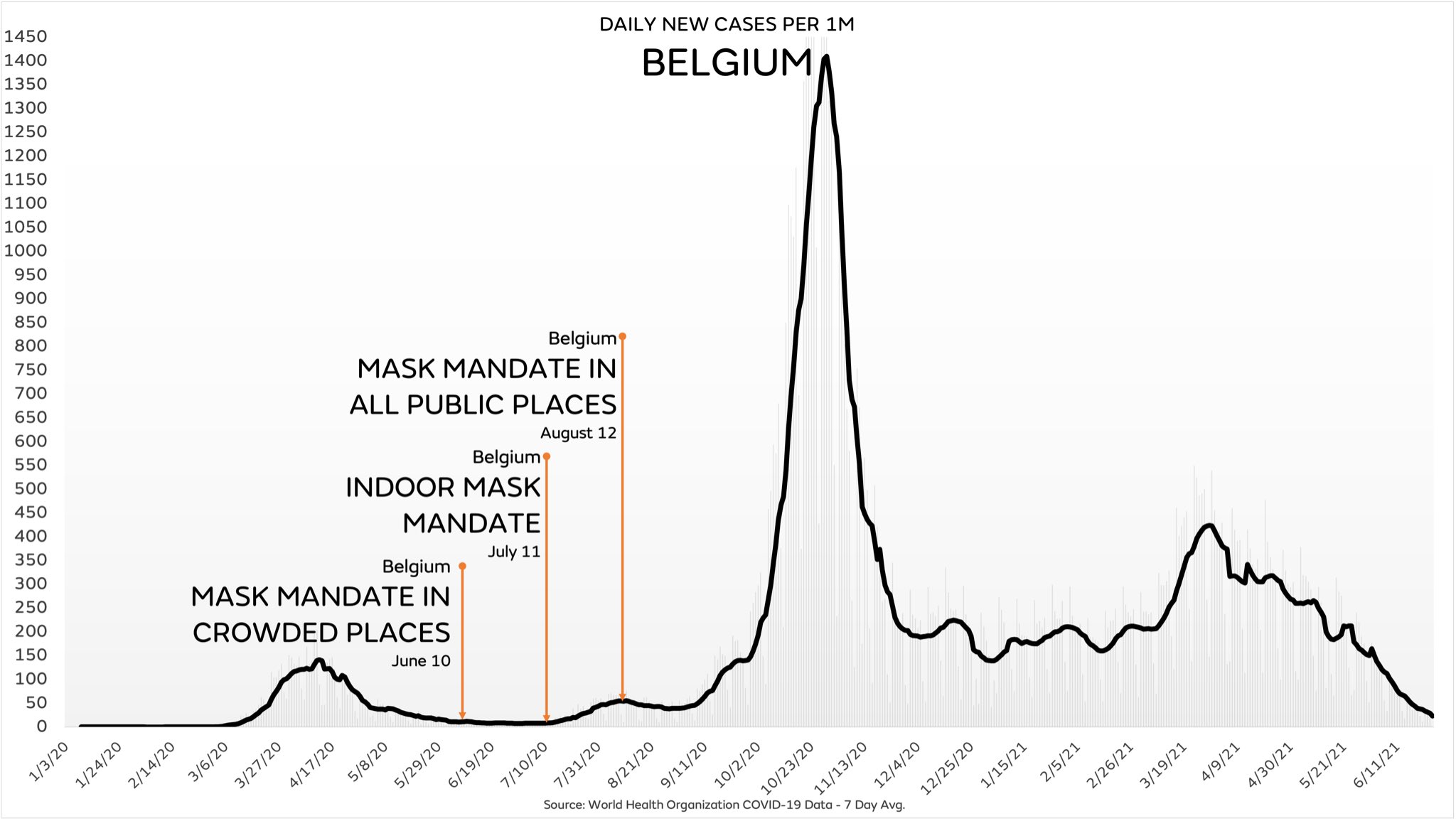

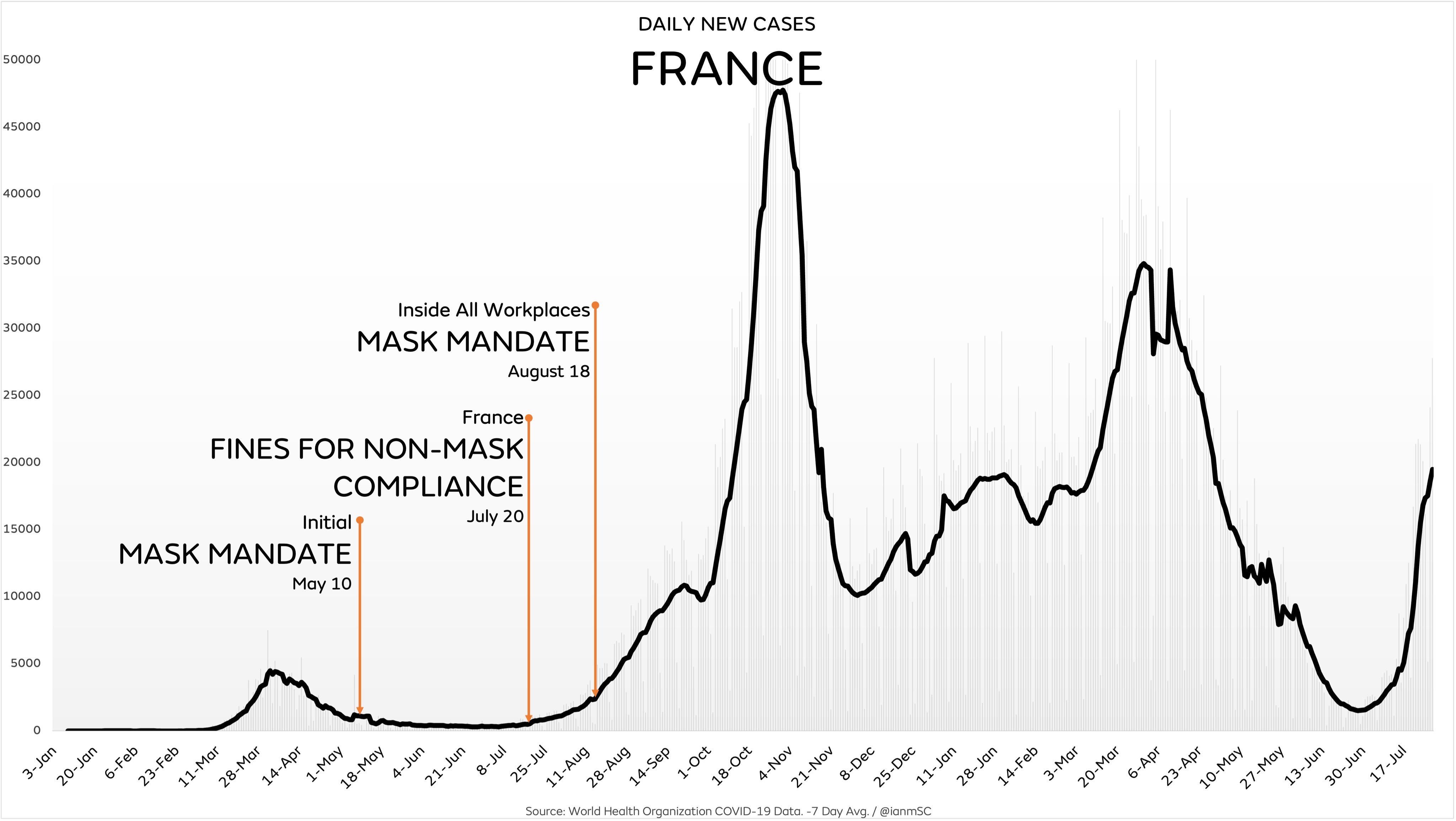

In many states, coronavirus infections strongly increased after mask mandates had been introduced. The following charts show the typical examples of Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Spain, the UK, California and Hawaii. Furthermore, a direct comparison between US states with and without mask mandates indicates that mask mandates have made no difference. (Charts: Y. Weiss)

For an updated version of these charts, see the postscript below.

C) Effectiveness of N95/FFP2 mask mandates

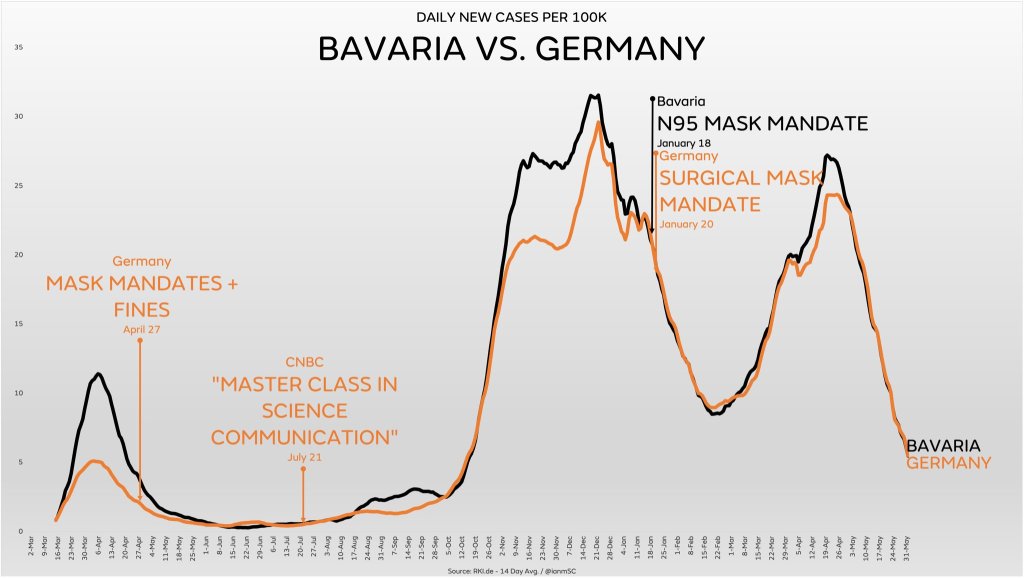

In January 2021, the German state of Bavaria was one of the first places in the world to mandate N95/FFP2 masks in most public settings. A comparison with other German states, which required cloth or medical masks, indicates that even N95/FFP2 masks made no difference.

D) Additional aspects

- There is increasing evidence that the novel coronavirus is transmitted, at least in indoor settings, not only by droplets but primarily by smaller aerosols. However, due to their large pore size and poor fit, most face masks cannot filter out aerosols (see video analysis below): over 90% of aerosols penetrate or bypass the mask and fill a medium-sized room within minutes.

- The WHO admitted to the BBC that its June 2020 mask policy update was due not to new evidence but “political lobbying”: “We had been told by various sources WHO committee reviewing the evidence had not backed masks but they recommended them due to political lobbying. This point was put to WHO who did not deny.” (D. Cohen, BBC Medical Corresponent).

- To date, the only randomized controlled trial (RCT) on face masks against SARS-CoV-2 infection in a community setting found no statistically significant benefit (see above). However, three major journals refused to publish this study, delaying its publication by several months.

- An analysis by the US CDC found that 85% of people infected with the new coronavirus reported wearing a mask “always” (70.6%) or “often” (14.4%). Compared to the control group of uninfected people, always wearing a mask did not reduce the risk of infection.

- Researchers from the University of Minnesota found that the infectious dose of SARS-CoV-2 is just 300 virions (virus particles), whereas a single minute of normal speaking may generate more than 750,000 virions, making face masks unlikely to prevent infection.

- Contrary to common belief, studies in hospitals found that the wearing of a medical mask by surgeons during operations didn’t reduce post-operative bacterial wound infections in patients.

- Many health authorities claimed that face masks suppressed influenza; in reality, influenza was temporarily displaced by the more infectious coronavirus. Indeed, influenza disappeared even in states without masks, lockdowns and school closures (e.g. Sweden and Florida).

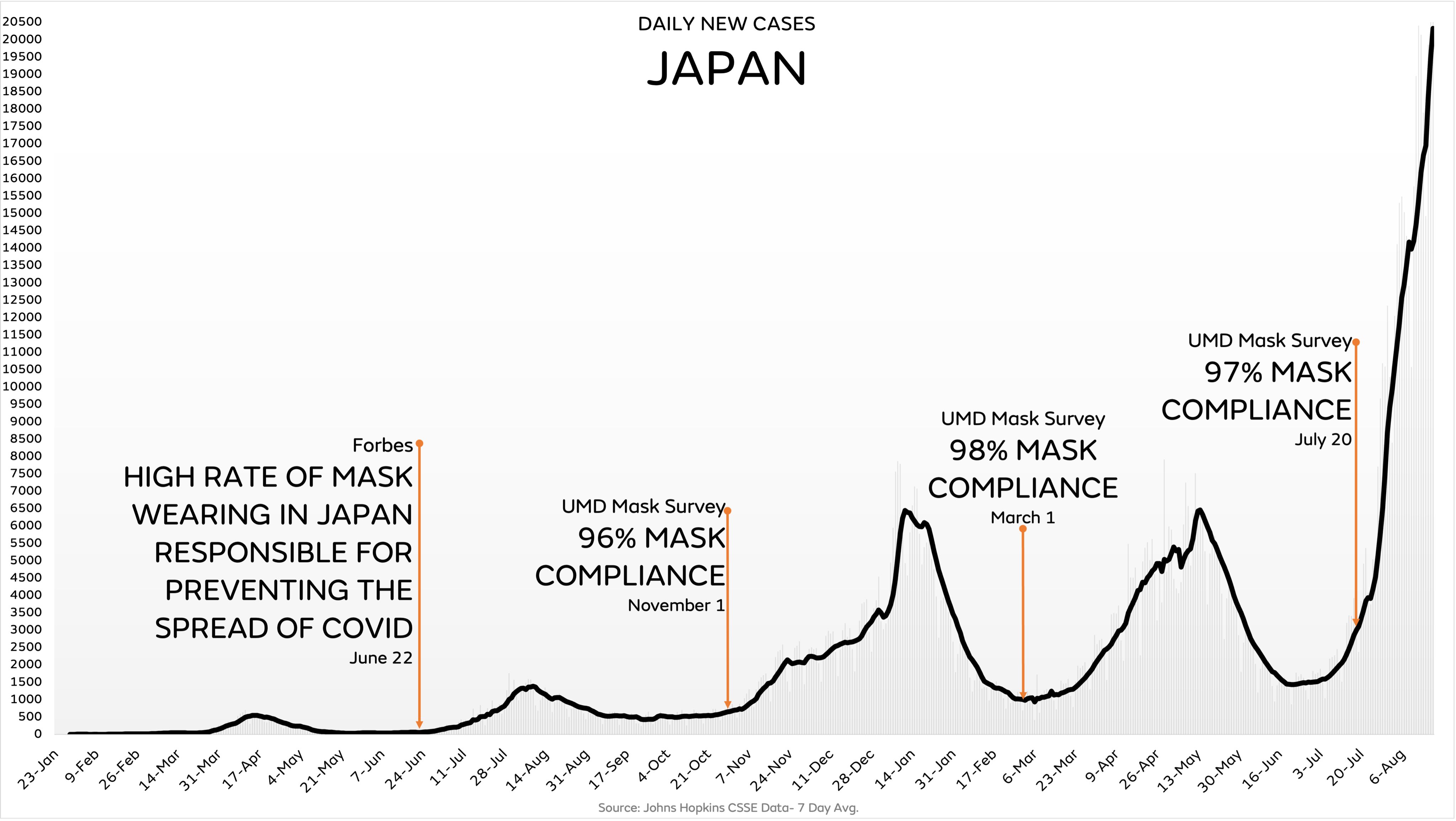

- The initially low coronavirus infection rate in some Asian countries was not due to masks, but due to very rapid border controls. For instance, Japan, despite its widespread use of face masks, had experienced its most recent influenza epidemic just one year prior to the covid pandemic.

- Early in the pandemic, the advocacy group “Mask for All” argued that Czechia had few infections thanks to the early use of masks. In reality, the pandemic simply hadn’t reached Eastern Europe yet; a few months later, Czechia had one of the highest infection rates in the world.

- During the notorious 1918 influenza pandemic, the use of face masks among the general population was widespread and in some places mandatory, but they made no difference.

E) The facemask aerosol issue

In the following video, Dr. Theodore Noel explains the facemask aerosol issue.https://videopress.com/embed/4egEyh2b?hd=1&cover=1&loop=0&autoPlay=0&permalink=1

F) Studies claiming face masks are effective

Some recent studies argued that face masks are indeed effective against the new coronavirus and could at least prevent the infection of other people. However, most of these studies suffer from poor methodology and sometimes show the opposite of what they claim to show.

Typically, these studies ignore the effect of other measures, the natural development of infection rates, changes in test activity, or they compare places with different epidemiological conditions. Studies performed in a lab or as a computer simulation often aren’t applicable to the real world.

An overview:

- A meta-study in the journal Lancet, commissioned by the WHO, claimed that masks “could” lead to a reduction in the risk of infection, but the studies considered mainly N95 respirators in a hospital setting, not cloth masks in a community setting, the strength of the evidence was reported as “low”, and experts found numerous flaws in the study. Professor Peter Jueni, epidemiologist at the University of Toronto, called the WHO study “essentially useless”.

- A study in the journal PNAS claimed that masks had led to a decrease in infections in three global hotspots (including New York City), but the study did not take into account the natural decrease in infections and other simultaneous measures. The study was so flawed that over 40 scientists recommended that the study be withdrawn.

- A US study claimed that US counties with mask mandates had lower Covid infection and hospitalization rates, but the authors had to withdraw their study as infections and hospitalizations increased in many of these counties shortly after the study was published.

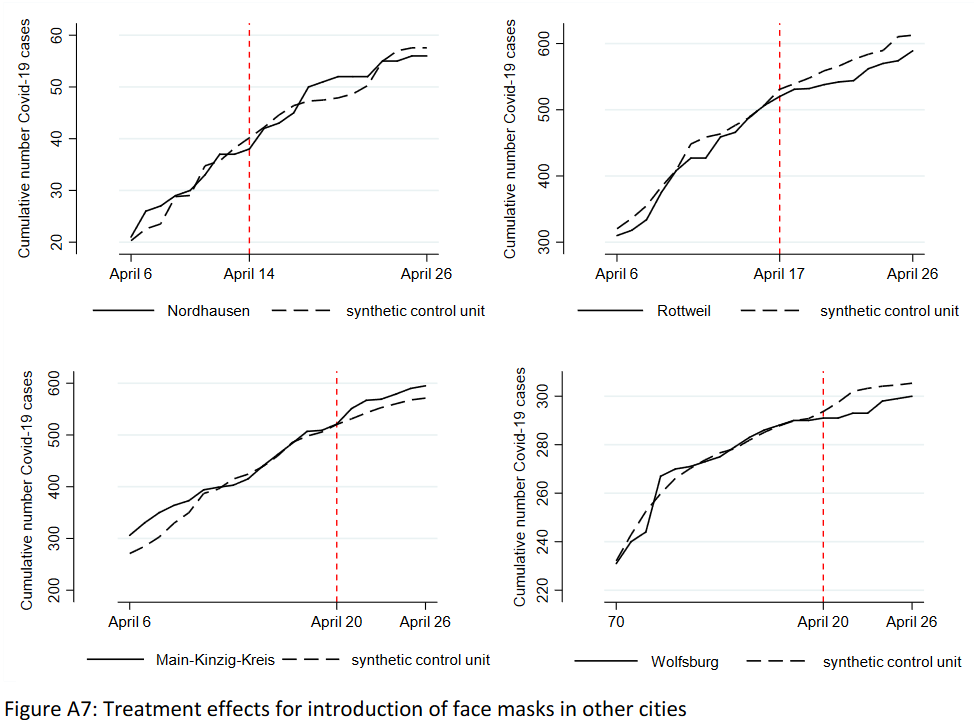

- A German study claimed that the introduction of mandatory face masks in German cities had led to a decrease in infections. But the data did not support this claim: in some cities there was no change, in others a decrease, in others an increase in infections (see graph below). The city of Jena was an ‘exception’ only because it simultaneously introduced the strictest quarantine rules in Germany, but the study did not mention this.

- A Canadian study claimed that countries with mandatory masks had fewer deaths than countries without mandatory masks. But the study compared countries with very different demographic structures and covered only the first few weeks of the pandemic.

- A review by the University of Oxford claimed that face masks are effective, but it was based on studies about SARS-1 and in health care settings, not in community settings.

- A review by members of the lobby group ‘Masks for All’, published in the journal PNAS, claimed that masks are effective as a source control against aerosol transmission in the community, but the review provided no real-world evidence supporting this proposition.

- A study published in Nature Communications in June 2021 claimed that masks reduced the risk of infection by 62%, but the study relied on numerous questionable modelling assumptions and on self-reported online survey results, not on actual measurements.

- A large study run in Bangladesh claimed that face masks “reduced symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections” by 0.08% (ARR) and only in people over 50. The study was designed and organized so poorly that it “ended before it even began”, according to one reviewer.

G) Risks associated with face masks

Wearing masks for a prolonged period of time may not be harmless, as the following evidence shows:

- The WHO warns of various “side effects” such as difficulty breathing and skin rashes.

- Tests conducted by the University Hospital of Leipzig in Germany have shown that face masks significantly reduce the resilience and performance of healthy adults.

- A German psychological study with about 1000 participants found “severe psychosocial consequences” due to the introduction of mandatory face masks in Germany.

- The Hamburg Environmental Institute warned of the inhalation of chlorine compounds in polyester masks as well as problems in connection with face mask disposal.

- The European rapid alert system RAPEX has already recalled over 100 mask models because they did not meet EU quality standards and could lead to “serious risks”.

- A study by the University of Muenster in Germany found that on N95 (FFP2) masks, Sars-CoV-2 may remain infectious for several days, thus increasing the risk of self-contamination.

- In China, several children who had to wear a mask during gym classes fainted and died; autopsies found a sudden cardiac arrest as the probable cause of death. In the US, a car driver wearing an N95 (FFP2) mask fainted and crashed due to CO2 intoxication.

Video: A mask-wearing, 19-year-old US athlete collapsing during an 800-meter run (April 2021):https://www.youtube.com/embed/AmEzfG3uJX8?version=3&rel=1&showsearch=0&showinfo=1&iv_load_policy=1&fs=1&hl=en-US&autohide=2&wmode=transparent

Conclusion

Face masks in the general population might be effective, at least in some circumstances, but there is currently little to no evidence supporting this proposition. If the coronavirus is indeed transmitted via indoor aerosols, face masks are unlikely to be protective. Health authorities should therefore not assume or suggest that face masks will reduce the rate or risk of infection.

Postscript (August 2021)

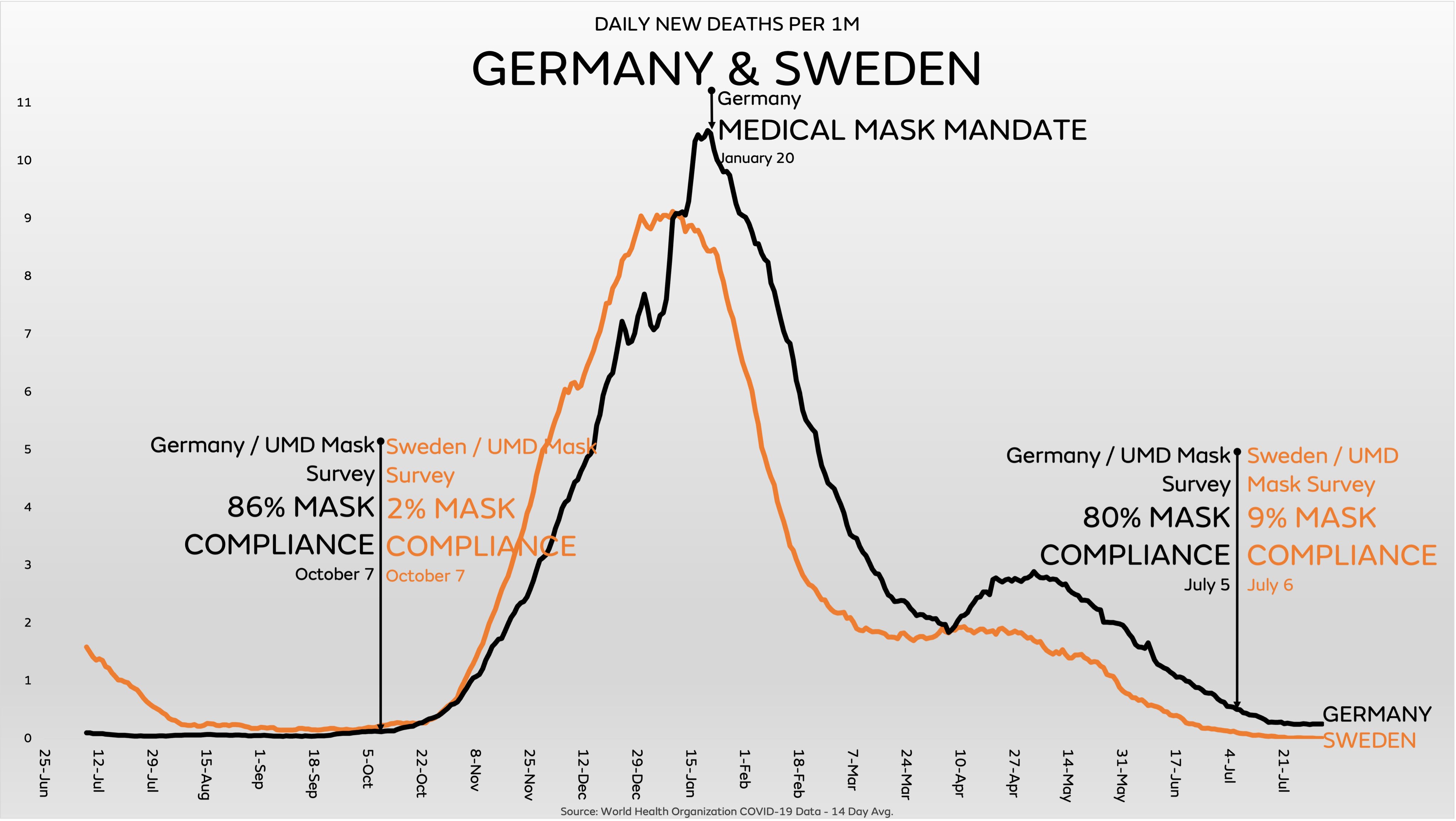

A long-term analysis shows that infections have been driven primarily by seasonal and endemic factors, whereas mask mandates and lockdowns have had no discernible impact (charts: IanMSC).

Further reading

- The face mask folly in retrospect (August 2021)